How to Resolve Conflict in the Workplace

Turning Tides: An Agile Coach’s Journey through Workplace Conflict and Resolution

It was a Thursday afternoon, just like any other in the bustling, open-concept office of Swift Software Inc. As an Agile Coach, I was overseeing multiple teams, all engrossed in their tasks. Amid the usual hum of industrious chatter, a sudden sharp exchange of words grabbed my attention. It came from Team Phoenix, known for their remarkable synergy and usually seamless operations.

Their disagreement quickly grew into a full-blown conflict, involving the entire team. The room was soon divided, tension thick in the air. Work came to a standstill, replaced with heated discussions, and I knew something had to be done.

As a seasoned Agile Coach, I had navigated the turbulent seas of conflict before. I knew that this confrontation, if dealt with correctly, could lead to growth and innovation rather than discord. Here’s the step-by-step approach I used, which might come in handy for you too.

Recommended e-learning course: Navigating Conflicts

Definition of Conflict

The big difference between disagreements and conflicts is that two people having a disagreement can remain good friends or colleagues, their relationship remains intact and contact is upheld. Sometimes they may find themselves even strengthened by such differences. In conflicts, relationships often turn sour and communication ends.

Conflicts are disagreements that lead to tension within and between people, and conflict in the workplace is no different. The disagreement concerns an issue, whereas the ensuing tension affects the relationship. Thus, a conflict always has the duality of dealing with both an issue and a relationship. Effective conflict resolution must therefore address both. If we do not deal with the issue at hand, solutions will be short-lived. If we do not deal with the affected personal, human relationship, tension between those in conflict will remain.

While issues being disagreed upon are often concrete and tangible, making it easier to identify what lies at their core, relationships between people present the most complex element in a conflict. As an added complication, our capacity for the required empathy and finesse to resolve interpersonal conflict may vary from day to day.

Recognizing the Conflict

The first step is to recognize that there is a disagreement. It’s easy to ignore or avoid it in the hope that it would go away on its own, but my experience has taught me that this rarely happens. Instead, if problems are not addressed directly, they tend to linger and escalate. Recognizing the problem early provides for a more proactive approach to conflict resolution.

Understanding the Nature of the Conflict

It is critical to understand the fundamental cause of a disagreement. Is it a miscommunication? Conflicting priorities? Conflicting personalities? Different perspectives can contribute value to a team, but they can also lead to conflict if not managed properly. Identifying the true source and its level of escalation are the first step towards fixing the problem.

Five Dimensions of Conflict

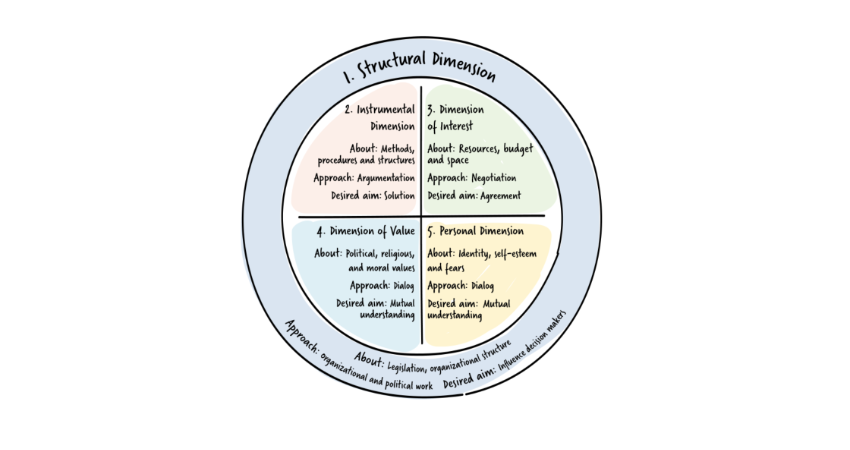

When people are in conflict, it usually means that they have a need that has not been met. This need is usually linked to one or more of five different dimensions: Structural, instrumental, interest, value or personal. Different dimensions present different challenges. It should be noted that conflict in the workplace may span more than one dimension; in fact, most conflicts are embedded within two or more dimensions.

- The structural dimension: The surrounding framework that we live and work in. Conflict resolution will not change the structural dimension, but it may reveal areas that need attention to prevent future conflicts. Grassroots movements or other democratic measures can influence decision-makers in structural conflicts.

- The instrumental dimension: Conflicts with an instrumental basis are typically concrete. For example, two parties disagree on a task. Instrumental disagreements usually keep people focused. Disputes typically end peacefully. Conflicts escalate only if the disagreements are rooted in other dimensions or if great animosity is present. Compromises are the best ways to solve instrumental problems.

- The dimension of interest: This dimension is centered on resources: money, time and space for instance. Power and influence can also be resources that are fought over. When dealing with the dimension of interest, a reasonable approach is to negotiate in order to reach an agreement on the division of resources.

- The dimension of value: By values we mean personal and cultural values. These values are something that you are willing to fight for. They define what is right and wrong, what one can or cannot do. Conflicts that escalate are often embedded in either the dimension of value or the personal dimension as these dimensions are non-negotiable. The goal is to reach a greater understanding of the other party’s position. When one understands the reasons and background for another person’s values, they are much easier to accept or tolerate.

- The personal dimension: This dimension causes numerous disagreements. Emotions and fears rule here. “Am I valued?” “Am I being excluded?” Identity, loyalty, rejection, and self-esteem are personal. As with value, open discourse, appreciative inquiry, and non-violent communication are optimal for the personal dimension.

These dimensions are inextricably linked. When colleagues are in conflict over their workspace, it may appear to be an instrumental conflict, but it may also be rooted in interests and a fight for what one party views as fairness, power, or the need to be recognized. When attempting to resolve a conflict, an examination of its dimensions might provide insight into where to begin or where to focus one’s attention.

Conflict Escalation

Conflicts can escalate if they are allowed to develop without intervention or if affected parties continue to fuel the fire. Personifications, accusations, harmful deeds, or worse can emerge as conflict intensifies. The issue that sparked the disagreement gets increasingly hazy, and what matters now is how wrong the other person is. Communication breaks down; one speaks of, instead of to, the other person. Only the antagonistic relationship remains.

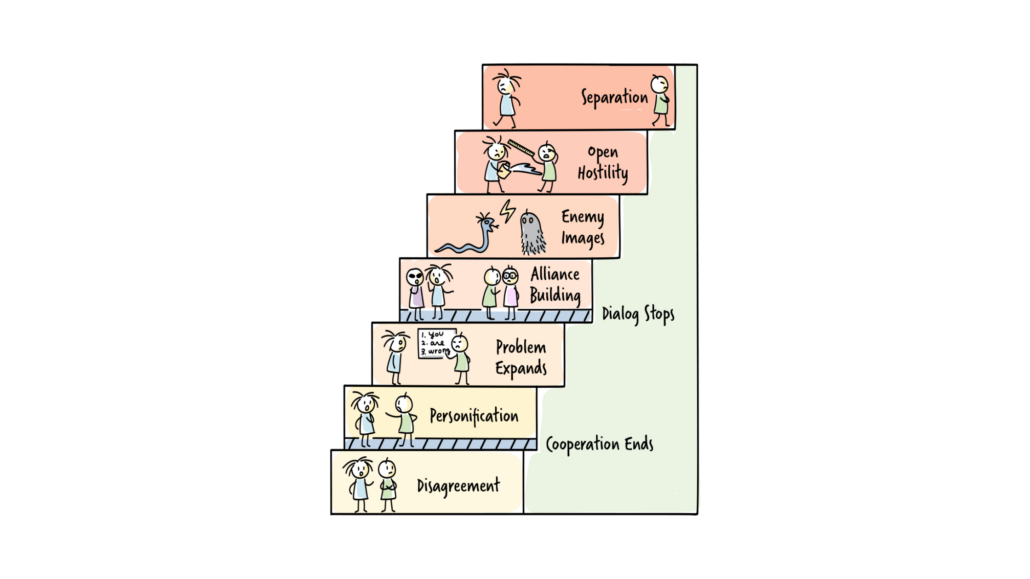

A look at the seven stages of conflict escalation gives us a better understanding of the different levels of maturity and phases of conflict.

The Seven Levels of Conflict Escalation

1. Disagreement: “We just don’t want the same thing”

No conflict exists yet, only a disagreement. Both parties try to solve it reasonably. However, the relationship may deteriorate if issues are not resolved. When someone violates a professional or personal boundary, the other party reacts and escalates.

The Disagreement-Personification border is crucial. After passing it, participants may become uncooperative and tense. One party blames, threatens, and insults the other vocally, gesturally, or physically. The other party usually follows.

2. Personification: “It’s your fault”

Once conflict escalates, focus shifts from the issue to the persons involved, making them and their personal failings and faults the issue. Negative emotions such as fear and confusion begin to interfere with communication between parties. Doubts about the intentions of the other party may arise and make it difficult to think clearly about the issue.

3. The problem expands: “This is not the first time they have done this!”

Old differences that are unrelated to the original issue are brought up.

The border between The Problem Expands and Alliance Building is another important transition as the crisis grows. Dialog ceases, ending the relationship. Resolving issues requires communication. Thus, maintaining a relationship, however tough, is crucial. We understand the need for time off to think and reflect.

4. Alliance building: “Let the gossip start”

Negative emotions limit thinking. Both parties misinterpret each other’s words. Hear selectively. One wants allies to affirm one’s stance and the other’s mistakes. Communication seems pointless and misconstrued.

5. Enemy images: “They’re no good”

One’s thought processes become increasingly entrenched as contact and communication end. One’s perspective gets so one-sided that it’s hard to see the other’s positive points. Before acts of violence, dehumanization is often used to prepare for them.

6. Open hostility: “It’s them or us”

It is no longer human. They cannot be sensible persons suffering from conflict like you. Evil, unreasonable, and unredeemable. This distinction allows psychological and physical aggression. Next, “the ends justify the means” arises. Along this road, blatant hatred becomes more regular, severe, and acceptable.

7. Separation: “Let’s get away”

Co-existence is no longer possible. The parties involved must be separated. Conflict remains unresolvable.

Dealing with Conflicts

Conflicts do not have a life of their own. Conflicts are the result of how people interact and the issues they disagree on. There are a number of ways or techniques for dealing with conflicts. These strategies are influenced, among other things, by your understanding of conflicts in general.

Open Communication and Active Listening

Creating an environment that fosters open communication is essential. As an Agile Coach, I encourage team members to express their thoughts and feelings using “I” messages, like “I feel overlooked when my ideas aren’t considered”, instead of accusatory “you” messages. I’ve found this approach reduces defensive reactions and fosters understanding.

Active listening is also essential. It’s important to listen, reflect, and respond without interrupting. This not only helps clarify the issues but also makes the parties involved feel heard and understood.

Identifying Common Goals

I always remind my team that despite any differences, we share common goals. By refocusing on these shared objectives, we can turn workplace conflict into a constructive discussion on how to best reach our targets.

Finding a Compromise or Consensus

Once everyone’s perspective is understood, we work together to find a solution. This might involve compromise or reaching a consensus where everyone feels their views have been considered.

Resolving Conflict within a Group

When dealing with conflicts in a group setting, it can be useful to perform a flow analysis. A flow analysis views the group being analyzed as a whole system, where each individual is interconnected with the others. The result of the analysis is not directed at any one individual but at the group as a whole. To perform a flow analysis, the group should sit in a circle and ask each member of the group three questions to be answered one-by-one:

- How do you disrupt the flow of this group?

- Why do you do this?

- What do you need in order to be willing to change your strategy?

Every question makes the round once before moving on to the next. Each answer is written on a piece of paper and checked for accuracy with the respondent. After the three rounds, the group is divided into three sub-groups, to tackle a question each question. Each group must then condense the answers to their particular question into as few sentences as possible, without loss of meaning. The result of this process is how the group as a whole believes flow is stopped, why it is stopped and what needs to be done in order to prevent it from being stopped. The process is conducted in complete openness.

Conflict Mediation

Mediation is a voluntary and confidential method of solving conflicts. An impartial third party (the mediator) is brought in to help the two conflicting parties reach a solution that both find satisfactory. The parties are not obliged to reach an agreement or solution and everyone involved, including the mediator, has the option to terminate the process if they wish to. The goal of the process is for both parties to take ownership of the conflict.

Those in conflict in the workplace have a chance to speak their truth and have that truth heard and are in turn required to listen and hear the other side’s truth as well. Hopefully, this results in a restoration of the dignity of both parties and the relationship between them, as well as lasting agreements concerning future interaction.

Conflict mediation generally goes through five steps:

- The first, opening step of the process consists of the involved parties and the mediator going over the issue at hand and determining the source of conflict. The mediator then elaborates briefly on the process itself and the different roles within, while confirming their own impartiality. It is important at this stage to both reassure everyone that everything being discussed is entirely confidential and that the whole process is voluntary for everyone involved. It is advisable to take this opportunity at the start to establish the purpose of the mediation and the ground rules for the process, while taking practical matters into consideration, such as the allocated time frame or possible follow-ups. Only when consensus on the framework for the mediation has been reached should the process move on to the next step.

- The next step involves gaining an overview of all parties’ accounts of the issue at hand, fostering an open dialog. All aspects of the issue are relevant, from facts to feelings, each parties’ interests and needs.

- Once details of the conflict have been established, the next goal is to reach a consensus regarding the problem at hand. Often when conflicts have escalated, there is no longer a single core issue, but a variety of needs, grievances and demands on either side. The goal in this step is to establish which of these issues need to be dealt with.

- The fourth step follows up on the established focal points and seeks out possible solutions each side can support. This often involves brainstorming solutions for both sides to co-sign on.

- As a final step, the solutions need to be presented and an agreement needs to be reached by all parties.

Follow Up

Resolving a conflict doesn’t stop at finding a solution. I make it a point to follow up, ensuring the agreed-upon solutions are being implemented and the conflict hasn’t resurfaced.

Foster a Positive Work Environment

To prevent conflicts in the first place, I strive to foster an environment of respect, open communication, and collaborative problem-solving. A positive, supportive work culture can often preemptively address many potential conflicts.

Looking back at that Thursday afternoon, I remember how the heated exchange between Sarah and Alex morphed into a turning point for Team Phoenix. The conflict, though initially disruptive, led to more open discussions about each team member’s ideas. Alex’s design changes were partially implemented, taking into consideration Sarah’s concerns about deadlines. The team learned to view conflict not as a destructive force, but as an opportunity to innovate and improve.

In the end, we used the conflict to better the project and strengthen our team’s bond. It was a profound reminder that, when navigated correctly, conflict can be a catalyst for innovation, fostering a more open and communicative team environment.

As Agile Coaches, we have an opportunity to transform the way our teams perceive and handle conflict. Let’s strive to guide them through the stormy seas of disagreement, towards the calm waters of understanding and collaboration. After all, it’s through facing these challenges that our teams learn, grow, and ultimately, soar to new heights.

Want to back your knowledge with a certification?

Try our online course on Navigating Conflict to learn more about this topic and earn a certificate that you can share on your resume or LinkedIn.

T