Effective decision-making is the lifeblood of any business, and is important in any context. Being able to make the best decisions as quickly as possible can make the entire enterprise run more smoothly. Agile decision-making in particular encourages leadership at all levels of organizations, which is highly motivating for your teams. Here are six Agile decision-making models to try out in your organization.

Recommended for you: Help your team’s processes run more smoothly with the Agile Facilitation Foundations online course

Why is decision-making so important in an agile organization?

In Agile teams, or those striving for agility, decision-making is not based on the command and control of management. It is a collaborative and consensus-based process. When you are trying to manage self-organized, responsible, accountable teams, decision-making is the domain of groups of people.

Decisions need to be coherent in the organization, which is an exciting and complex puzzle. Think of it like a rowing team: each person is rowing, making different decisions about each stroke, but ultimately moving in the same direction. It’s about forward momentum and coherence. Decision-making frameworks or models help people understand the scope of their decision-making power so that they are able to make decisions without barriers.

How is decision-making in agile organizations different from traditional hierarchical workplaces?

In traditional organizations, it’s about the manager making the decision, while others follow. In more agile organizations, everyone has a voice and opinions are encouraged. Because of the collaborative nature. The Agile manifesto’s principles imply that teams are making their own decisions about their work. These are visible to the stakeholders around them, rather than waiting for team leaders. It wastes time.

What is the effect of slow, poor, or disorganized decision-making?

In an agile organization, a core focus is to avoid waste. Poor, slow decision-making creates a lot of wasted time and effort, and this is what we hope to avoid. Empowering teams to make their own decisions also has the effect of a faster time to market.

Six decision-making models to help you move forward

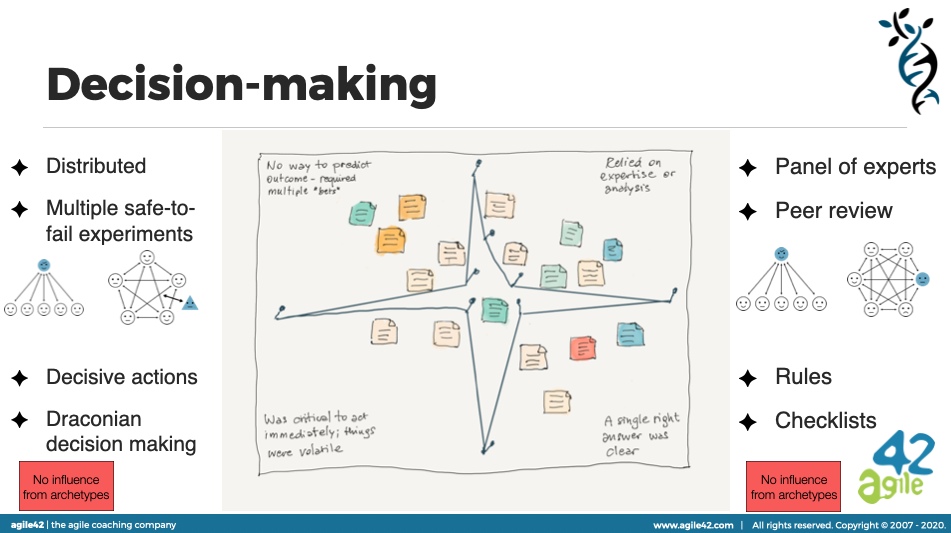

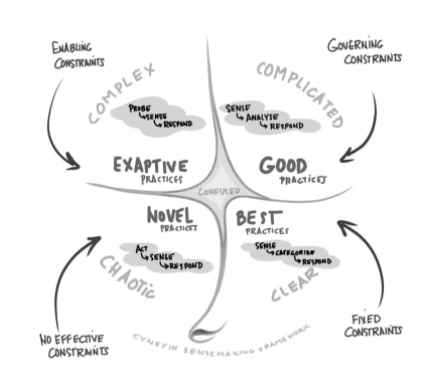

Cynefin Framework

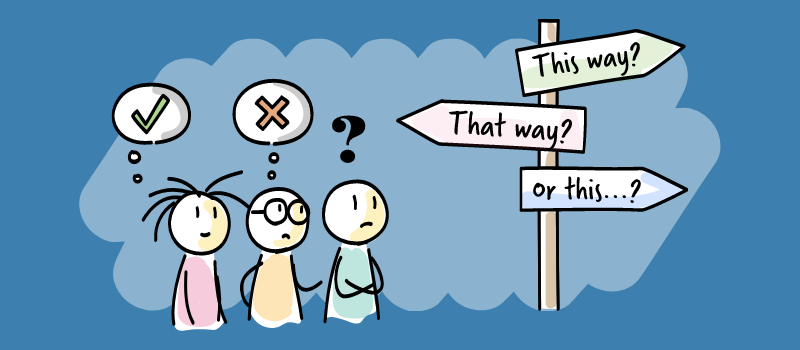

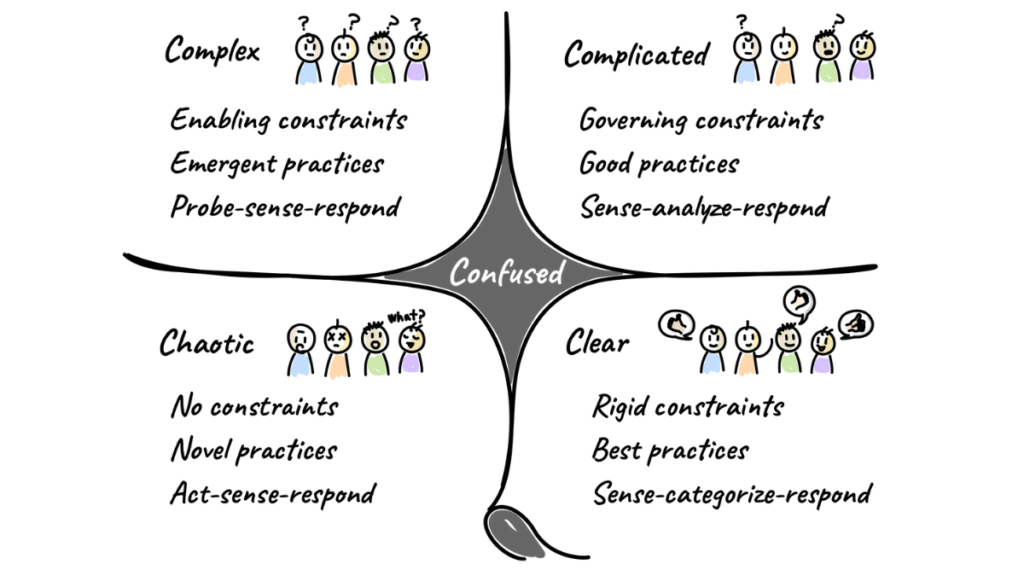

At agile42 we have a favorite framework for sense-making, which we consider the first, essential step of any effective decision-making. The Cynefin Framework is all about making sense of the domain and situations. “Cynefin” is a Welsh word without a real English equivalent, but it translates roughly to “a place of your multiple belongings”. The framework has five decision-making contexts, or domains: clear, complicated, complex, chaotic, and confusion. Cynefin is most useful when you need to make sense of a problem before making a decision about it.

Recommended for you: Learn the Cynefin Framework in our CAL training

How to use it: Depending on which domain we’re in, there are different appropriate actions. The clear and complicated domains are considered “ordered”; while the chaotic and complex domains are “unordered”. The aim is to place the situation in the correct domain, which allows you to make sense of it and be better-equipped to make the right kind of decision to move forward. For more detail on using this method, read our blog on the Cynefin Framework.

SWOT analysis

SWOT analysis is possibly the most-used, most traditional decision-making framework, but it is still highly relevant. It is centered on a desired end state, which needs to be clear for the framework to be effective. This method works very well when used hand-in-hand with Cynefin, especially in the Complicated domain. It is a great way to decide what needs to be done next, after making sense of the situation.

How to use it: The team comes together to analyze the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats of a given situation. This process ideally involves a big miro board, or lots of sticky notes, with silent brainstorming. The facilitator then decides what to do to move forward. They may use dot voting to identify what is important in each quadrant, then we discuss, analyze, and add clarity to help teams make their decisions.

Decider protocol

The Decider Protocol is a way to make unanimous decisions. A decision is proposed, and there is an iterative voting process which continues until consensus is reached. It can be time-consuming, but is a useful, structured way to get the whole team in agreement.

How to use it: There is a proposer, who proposes a decision to the group. The proposal needs to be short, clear, to the point and actionable. It focuses on one single issue. Once the proposal is made, people can think about it for a few minutes. Then the team votes, on the count of three. They either hold up a thumbs-up (100% behind this), a thumbs-down (cannot support this) or a flat hand (support with reservations). On the count of three, they hold up their thumbs at the same time. The no’s and maybe’s then have the opportunity to share their doubts and concerns, which are discussed with the group. They are asked, “what will it take for you to get behind this?”. The proposal is modified to accommodate this input, and then the process begins again, repeating until there is full consensus.

Fist of five

Fist of Five is another agile decision-making model to use when you need consensus. It is most popular in Scrum teams for making fairly informal daily decisions.

How to use it: The facilitator presents a decision that needs to be made. Each person in the team votes by holding up a number of fingers at the count of three. Five fingers indicates full agreement; four fingers means the team member is happy with the decision; three fingers indicates support with no major concerns; two fingers expresses reservations that need further discussion; and one finger means the team member is opposed.

Next, the team must discuss everyone’s reasonings and reservations, which fosters important discussion around the pros and cons. After everybody has a chance to share views, the proposal is adapted and a new vote takes place, repeating until there is a consensus about whether to move forward or scrap the idea.

Forced ranking

Forced ranking helps to make difficult decisions when prioritizing a list of items.

How to use it: The team starts with a list of no more than 10 items. Each person assigns a numeric value to each of the items (only one value per item). This must be made visible on a flipchart or board. The facilitator collects the numeric of the “votes,” and adds the numbers up. Items with the most votes go to the top, while others down in order.

Relative estimation

Relative estimation is used when teams need to estimate tasks and user stories.

How to use it: Items are placed on a board or wall. Each individual goes to the list of items and places it according to what they think is most important, taking into account the effort required. Each person will shuffle things up or down according to their own ideas. This is done in silence first, but then people need to discuss their thoughts and reasoning. It can be difficult to reach a final consensus, and if so, Fist of Five can be used once you’ve narrowed it down.

How do you know when you’re using the right decision-making model?

Teams should be taught as many decision-making models as possible. The more resources and tools they have at their disposal, the easier it is to determine which tools are most useful in any given scenario. Cynefin is always a great starting point for sense-making, and these models can be used alone or in combination with one another. A key aspect of efficient decision-making is ensuring that the team has all the information they need, and if you’re struggling to reach decisions, that could be the cause. A neutral party to facilitate the decision-making process is also valuable.