What impact have you been able to observe on organisations when COVID hit?

One thing that has been really noticable for me since the start of the pandemic just over a year ago, and the different responses organisations have taken, is that the organisations that previously invested a lot more in their individuals, their teams, and their autonomy, have really responded and coped much better. They had less disruption than the organisations that had effectively paid lip service to the agile values & principles. Those organisations have tended to resort a lot more towards micro-management, status updates and check-in meetings.

How has leadership been affected by the shift to remote work?

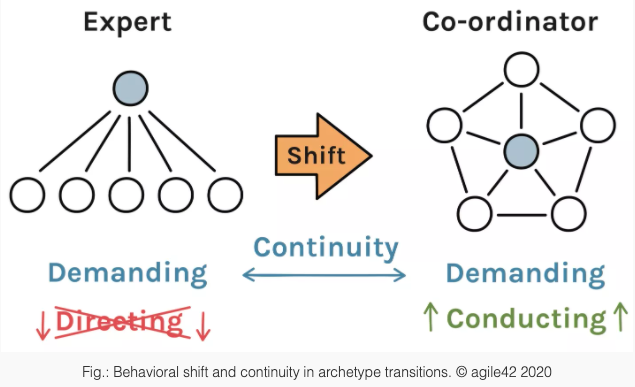

Essentially leadership hasn’t really changed especially if we work in a complex domain as complex work requires greater autonomy and autonomy still requires competence, confidence and conditions for success. So the job of a leader is to help their team get to greater competence, develop confidence and to create the conditions where they can be autonomous.

Can you give any advice about what to focus on to better lead remotely?

I’m going to talk about a few areas of many that great leaders can focus on in order to make remote leadership more effective.

Isolation

The first one is “isolation”. Now it might sound strange for me to even mention this, as it is obvious that while we’re all working more remotely and we’re not in the office seeing each other day-to-day we are bound to feel more isolated. I think it’s a really important thing to be aware of as we are missing out on a lot of things that we would consider to be our innate human needs.

The first one is “isolation”. Now it might sound strange for me to even mention this, as it is obvious that while we’re all working more remotely and we’re not in the office seeing each other day-to-day we are bound to feel more isolated. I think it’s a really important thing to be aware of as we are missing out on a lot of things that we would consider to be our innate human needs.

We are social animals and by being forced apart from our colleagues we are missing out on the small talk, on the connection, the collaborative problem solving and the informal chats that would normally make up a large part of our day. When we miss out on some of those innate human needs that we yearn for as social animals, we are generally going to be struggling as human beings to be our best.

So as leaders we need to be aware of that and regularly check in with people to make sure that their needs are being met. Notice that I said “checking in” on people. It is very, very different to “checking up” on people. We don’t need to check up on them, because as leaders we know that people want to be successful, we know that given the choice between being productive or unproductive, people would choose to be productive.

Burn-out

The second aspect is something that has been talked about quite a lot and that is “burn-out” or “overwhelm”. One interesting thing that I’ve observed is that the social cost of giving somebody else a task is significantly reduced if we’re not physically present with them. What I mean by that is it’s a lot easier for me to send somebody an email and ask them to do something than it is for me to look them in the eye and ask them to do something for me. As we are more remote, we are relying more on electronic means of communication. What we are seeing is a lot of people asking for a lot more things from others, leading to those people becoming overwhelmed.

The other important aspect when it comes to burn-out is the fact that we are spending a lot of our time on screens and in particular on conference calls, which it’s well documented on is more draining than in-person meetings for various reasons. When we’re spending our time on more draining mediums we’re going to make more mistakes; we’re going to take more shortcuts; innovation will be reduced; motivation will be reduced.

What can we do about it? Well, from my experience, a lot of the time we’re spending on these calls is around status updates and dependency management and usually that comes from being spread across multiple parallel pieces of work. The more pieces of work I am on at the same time, the more dependencies I have, therefore the more coordination I need to do. So one thing I can do as a leader, is help my people reduce the amount of things they are working on in parallel. Help people feel confident to prioritise, to focus, to say “no” or “not yet”. Or “yes” if: I can do that if you take this other piece of work off my hands.

Giving people the confidence and power to prioritise their workload and to focus, will reduce the amount of burn-out, or reduce the amount of fatigue and feeling of overwhelm. It has a secondary benefit of increasing our chances of getting things done, achieving a sense of completion which is so energising and motivating that it will give us more energy to get more stuff done. Focusing on less stuff, allows us to get more stuff done. That’s going to be a win-win for everyone.

Suspicion

The third area I would like to focus on is “suspicion”. Now this is an interesting one for me. Generally speaking, if we don’t see people, then we think less favourably of them. We start doubting their intentions. We start doubting their perceptions of us; we start doubting their interpretations; we start getting very suspicious about what they are doing and why they're doing it.

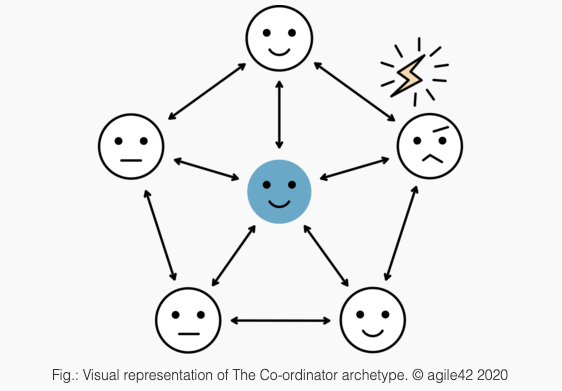

So as great leaders we can try to increase the opportunities for people to actually see each other, to get together, but not necessarily in a formal status sharing session. Perhaps informal coffee chats or building in time at the start of meetings to just talk about non-work stuff. Reinforce, re-establish that human connection again that will allow us to start thinking more positively of each other. As well as that, great leaders tend to role model this view of unconditional positive regard, choosing to believe that people are acting with positive intent. They take that action and they role model that to others to encourage others to choose to believe a positive interpretation of the possible interpretations.

So as great leaders we can try to increase the opportunities for people to actually see each other, to get together, but not necessarily in a formal status sharing session. Perhaps informal coffee chats or building in time at the start of meetings to just talk about non-work stuff. Reinforce, re-establish that human connection again that will allow us to start thinking more positively of each other. As well as that, great leaders tend to role model this view of unconditional positive regard, choosing to believe that people are acting with positive intent. They take that action and they role model that to others to encourage others to choose to believe a positive interpretation of the possible interpretations.

What is going to be different then, when leading remotely?

So there are many things that will be different while leading remotely, but essentially it’s the same. Essentially what we’re doing as leaders is we’re trying to find anything that is stopping our people, stopping our teams from being and doing their best. And once we’ve identified what those challenges are we can work out a way of solving them together and giving the teams the autonomy, the confidence, the competence and the conditions to be successful.

We hope this video gave you some food for thought during these rapidly changing times. Stay tuned for Part 2 later this month!

Watch the recording of Geoff's webinar on "Leading Remotely".

*Click here to read Part 2 blog post*

was used to the switch of context and the environment around us. We also learnt to adapt our behaviour and attitude accordingly depending on the specific client or employee. This is something that is very difficult to do when working remotely as we physically stay in the same place; we are likely dressed in the same way; we are looking at the same screen all day. So switching context when working remotely creates a significant amount of stress as we tend to think a lot more consciously rather than subconsciously about how we should behave.

was used to the switch of context and the environment around us. We also learnt to adapt our behaviour and attitude accordingly depending on the specific client or employee. This is something that is very difficult to do when working remotely as we physically stay in the same place; we are likely dressed in the same way; we are looking at the same screen all day. So switching context when working remotely creates a significant amount of stress as we tend to think a lot more consciously rather than subconsciously about how we should behave. In order to help people cope better with the situation and for you as leaders to understand how everyone is doing, you should consider having informal conversations. The informal conversations we used to have around the water cooler aren't as easy to have in a remote environment. As leaders we should consider having half an hour meetings with the team every week or every 2nd week to just talk about something other than work. Take your mobile phone and go for a walk outside - have a relaxing conversation. Check how people are doing; how their family is; what their interests are beyond work. Give them back that human touch we had in a physical environment.

In order to help people cope better with the situation and for you as leaders to understand how everyone is doing, you should consider having informal conversations. The informal conversations we used to have around the water cooler aren't as easy to have in a remote environment. As leaders we should consider having half an hour meetings with the team every week or every 2nd week to just talk about something other than work. Take your mobile phone and go for a walk outside - have a relaxing conversation. Check how people are doing; how their family is; what their interests are beyond work. Give them back that human touch we had in a physical environment. The first one is “isolation”. Now it might sound strange for me to even mention this, as it is obvious that while we’re all working more remotely and we’re not in the office seeing each other day-to-day we are bound to feel more isolated. I think it’s a really important thing to be aware of as we are missing out on a lot of things that we would consider to be our innate human needs.

The first one is “isolation”. Now it might sound strange for me to even mention this, as it is obvious that while we’re all working more remotely and we’re not in the office seeing each other day-to-day we are bound to feel more isolated. I think it’s a really important thing to be aware of as we are missing out on a lot of things that we would consider to be our innate human needs.

So as great leaders we can try to increase the opportunities for people to actually see each other, to get together, but not necessarily in a formal status sharing session. Perhaps informal coffee chats or building in time at the start of meetings to just talk about non-work stuff. Reinforce, re-establish that human connection again that will allow us to start thinking more positively of each other. As well as that, great leaders tend to role model this view of unconditional positive regard, choosing to believe that people are acting with positive intent. They take that action and they role model that to others to encourage others to choose to believe a positive interpretation of the possible interpretations.

So as great leaders we can try to increase the opportunities for people to actually see each other, to get together, but not necessarily in a formal status sharing session. Perhaps informal coffee chats or building in time at the start of meetings to just talk about non-work stuff. Reinforce, re-establish that human connection again that will allow us to start thinking more positively of each other. As well as that, great leaders tend to role model this view of unconditional positive regard, choosing to believe that people are acting with positive intent. They take that action and they role model that to others to encourage others to choose to believe a positive interpretation of the possible interpretations.