Scrum roles

Scrum Roles

The Scrum Team’s primary focus is to make the best possible progress toward the Sprint goal, which is the single objective for the Sprint. Within a Scrum team, there are no sub-teams or hierarchies. Rather, the team is a self-organized and self-managing unit of professionals. In contrast to classical project management methods, Scrum doesn’t have a product manager or a team leader. Let’s dive into the different Scrum’s different roles and responsibilities.

Recommended e-learning: Learn about the different elements of the Scrum framework and why it works only in its entirety in our Scrum Foundations online course.

The Product Owner

According to the Scrum Guide, the Product Owner is accountable for maximizing the value of the product resulting from the work of the Scrum Team. How this is done may vary widely across organizations, Scrum Teams, and individuals.

Product Owner Responsibilities

This role also holds a lot of accountability, as the name suggests. The PO has three key responsibilities.

Recommended for you: Product Owner Online Short Course

Manage the Product Backlog

The Product Owner is usually one person who is accountable for effective Product Backlog management. The Product Backlog is an emergent, ordered list of what is needed to improve the product or service. This includes developing and communicating the product goal, creating and ordering product backlog items, and ensuring that the product backlog is transparent and visible at all times. As a result, they often have to prioritize work and backlog items by keeping the product goal in mind.

Stakeholder Management

Often the PO has to “fight on both sides”. The Scrum Team often works within a specific time frame (the Sprint). During the Sprint, the Product Owner often needs to deal with marketing, management, or customers in order to prioritize work and maximize value. The PO must be an excellent communicator, as they must be in contact with all stakeholders, sponsors, and the Scrum team throughout a project.

Return on Investment

The Product Owner is also responsible for the return on investment (ROI). They validate the solutions from the end-user’s point of view and verify whether the quality is acceptable or not.

Product Owner vs Product Manager

Typically speaking, product managers are strategic and focus on the product’s vision as well as the company’s objectives and the market. Product Owners, on the other hand, are more tactical and focus on fulfilling a product vision by managing backlogs and working in cross-functional teams. A good Product Owner needs to be able to take responsibility, as the name suggests, for the success or failure of a project, which means they need to communicate effectively and juggle people’s expectations.

Photo by SHVETS production

The Scrum Master

The Scrum Master (SM) is accountable for establishing Scrum as defined in the Scrum Guide. The SM helps to increase the team’s effectiveness by enabling continuous improvement and making sure that everyone understands the theory and practices of Scrum, both within teams and the whole organization.

Recommended Training: Certified Scrum Master (CSM) Certification

Scrum Master Responsibilities

According to the Scrum guide, “Scrum Masters are true leaders who serve the Scrum Team and the larger organization.”

Improve the Team’s Effectiveness

The Scrum Master should create optimal working conditions for the team and keep these constant throughout the Sprint. This includes making sure that the team follows the Scrum Framework and understands all the elements of Scrum, including the five Scrum Events. They should have a comprehensive knowledge of Scrum and be able to act as a servant leader by creating the ideal environment for teams to thrive.

Remove Impediments

A Scrum Master is tasked with creating an environment for teams to thrive. They should aim to get rid of all possible impediments – or problems – that might disturb the work of the team. Usually problems can be classified in three different categories:

- Problems the team cannot solve: For example, there may be a lack of necessary hardware or software, or a stakeholder such as a manager is making unrealistic demands of the team.

- Impediments related to organizational structure or strategic decisions: There are many examples of this. Perhaps the office or virtual workspace is not adequately set up to enable teamwork: maybe there is an unreliable internet connection, or meeting rooms aren’t available. Another common example is that the Scrum Master is viewed as being a project leader, and the team isn’t viewed as their equals.

- Problems related to the individuals: This may include technical issues like computer crashes, or delays resulting from team members needing to wait for input to complete a task they’re unable to handle alone.

The Scrum Master can’t and shouldn’t solve every problem alone, but they are still responsible for guiding the team towards solutions and removing impediments. This task often takes up a lot of time and requires great resilience and the ability to care deeply for the team.

Serve the Whole Organization

The SM should lead the organization in adopting Scrum. They should help employees and stakeholders enact and understand Scrum so that it can be successfully implemented. They may need to coach and advise in these instances.

Photo by Luca Calderone on Unsplash

Scrum Master vs Project Manager

The most obvious difference between a Project Manager and a Scrum Master is represented by the name itself. A Project Manager manages the project and sets the tasks, while the SM is in charge of ensuring that the team adheres to the Scrum framework. The Scrum Master does not interfere with the decisions of the team in terms of what they do, but acts as an advisor to the team when it comes to how they work. They only interfere when any participant in the project does not align with the principles of Scrum. A project manager, on the other hand, often gives directions and takes responsibility for the completion of tasks.

The Scrum Developers

The Developers, or sometimes simply referred to as the Scrum Team or development team, have all skills necessary to create a valuable Increment for each Sprint, and they self-manage.

Scrum Developer Responsibilities

This team typically consists of three to five people and the specific skills needed by the Developers are often broad and will vary with the domain of work, however, they typically share the same set of responsibilities within a Sprint.

Create a Plan for the Sprint

The developers do not simply receive tasks from a project leader; they are self-managing and decide how many User Stories they can accomplish in one Sprint themselves. They create a plan for the Sprint, the Sprint Backlog (which is composed of the Sprint Goal, the Product Backlog items selected for the Sprint) as well as an actionable plan for delivering the Increment.

Manage and Execute Their Work

The developers instill quality by adhering to a Definition of Done and work to ensure that they meet that standard. They may need to adapt their plan to reach the Sprint Goal and always hold one another accountable during the Sprint.

Scrum Developers Work Differently from Traditional Teams

Developers in a Scrum Team decide on their tasks and are responsible for the execution of them – the team becomes a manager. The Scrum Master does not need to delegate all the work and plan the project

Get The Most out of Scrum

Scrum is simple to understand, but it can be difficult to master. Scrum is purposefully incomplete: It just defines the rules of the game, like the rules of a sport. That’s one reason why Scrum is hard to master: you need to know so many things outside Scrum to make it work successfully.

And if you need help implementing Scrum in your organization, get in contact with us.

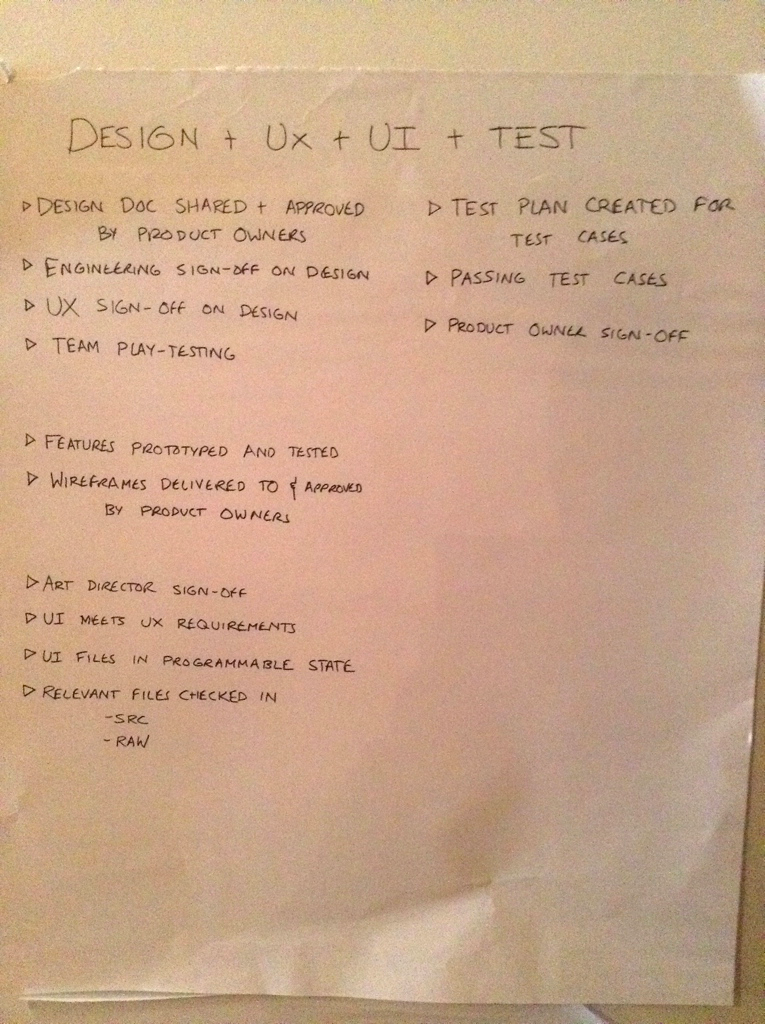

In many Scrum development teams, the design component is included in the team’s delivery. Either stories include mock-ups to be implemented as seen, or the cross-functional team includes a dedicated graphic designer/front-end designer who works as part of the cross-functional team to deliver a working product at the end of the sprint.

In many Scrum development teams, the design component is included in the team’s delivery. Either stories include mock-ups to be implemented as seen, or the cross-functional team includes a dedicated graphic designer/front-end designer who works as part of the cross-functional team to deliver a working product at the end of the sprint.