Why Coaching is Important

What is the Problem?

For people in 20th century organisations training was an obvious necessity. Just look at the still-classical organisation and see that it has a Training Department neatly tucked into the organisation chart just under Human Resources. (I hate that name…but I digress.)

Much changes in our post-industrial world where we think for a living, solving increasingly complex problems. Our paradigm for helping people be effective has not yet caught up.

What are the challenges?

-

- We are solving hard problems. This requires the brains of multiple people to be aligned and work collectively to emerge solution options.

-

- Failure remains stigmatised as something bad, rather than being recognised as an essential and desirable outcome of experimentation towards innovation.

-

- We remain stuck in authoritative command-and-control cultures that fail to unlock the potential of people.

-

- Employees acknowledge their own individual achievements, but less so their contribution to the result of a shared effort.

-

- Managers have not yet grasped their new role as enablers rather than directors.

-

- Most organisations reward individualism while hoping for teamwork.

-

- …add yours here…

What is Coaching?

Professional coaching may be described as a method for helping a person or a team to achieve specific goals in their professional lives. Paraphrasing Kaltenecker and Myllerup: the coach acknowledges that the person or team being coached already has the potential abilities required for reaching the goals and the assignment for the coach is to help unlock this hidden potential.

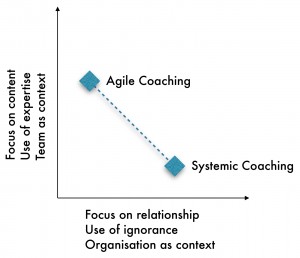

An “agile coach” often steps into acting as a teacher, advisor, mentor or role model. Here she applies her own expertise to lead and guide the individual or team in specific ways. Yet as soon as possible she should return to a coaching stance to return appropriate the power balance to the relationship.

The diagram depicts the difference between when the “agile” coach is relying on her own expertise of the content as distinct from the systemic coach using her own ignorance of the full organisational context and applying curiosity as a powerful helping tool to build relationship.

Why Do We Need Coaching?

Ask any successful leader and she will tell you stories about the people who have helped her, formally and informally, along her journey.

In order to learn and grow we require honest feedback. Without enough trust, honest feedback is unlikely to be offered and received in a productive manner. Traditional work environments do not provide safety for trust to flourish.

And in the modern work context that requires collaboration to produce good results we need to develop new “soft” skills that we were not taught at university or technicon. Teams and individuals need to learn to be vulnerable to one another.

However it is not a given that we will ask for help. There are hard questions to answer, for example:

-

- How do I recognise when I or my team needs help? Am I even capable of knowing what it is I don’t know (my blind spots)?

-

- Why would my boss pay me a salary when I need outside help to do my job?

-

- How does asking for help make me feel? I have to “lose face” to accept help from another.

-

- …add your own…

In the South African cultural context where “cowboys don’t cry” and “boer maak ’n plan” it can be particularly hard to ask for help. And in the “controlling” and “competitive” styles of organisational cultures that still predominate worldwide it can be seen as a sign of weakness.

So many of us live with an unhealthy tension between needing help from others in order to grow, and the uncertainty about whether or when it’s okay to ask.

The coach as trusted external party is well-skilled and well-placed to facilitate the necessary conversations to help teams grow trust, deal with conflict and offer commitment that in turn lead to increased accountability and improved outcomes.

An Economic View

In work over nine years with more than 100 teams we have observed a marked difference between the extent and the pace of growth of individuals and teams that have received coaching and those who have “gone it alone” after, perhaps, a two-day training class.

An analysis of our own data shows a correlation between “performing” teams and the quantum of help. The sweet spot seems to be between one and two days of coaching per team member during the first year of transition. To be clear this includes all facets such as advising and organisational development. Our data does differentiate between individual and team coaching, yet clearly there is a need for both.

Benefits we have observed during and after coaching include:

-

- Happier and more engaged team members

-

- Reduced staff turnover

-

- An increased sense of “we”

-

- An increase in self-confidence and independence

-

- Increases customer and stakeholder satisfaction through value delivery

-

- Increased throughput and decreased “time to market”

-

- Increased transparency and predictability

When asked how soon the benefits exceeded the costs, many clients have experienced improvement within a few weeks and the classic “J-curve” of change has not been felt. And it is not uncommon to hear “we have doubled/halved X compared with last quarter/year”.

Adding Perspective

Before we conclude that coaching is some “magic elixir”, let’s be clear that contexts differ and it is hard to attribute causality to a single element. Nevertheless we have many times heard “we should have got coaching earlier and had more of it”.

As Weick and Sutcliffe remind us in their excellent book about High Reliability Organisations, it is “a sign of strength to know when you’ve reached the limits of your knowledge and know enough to ask for help”.

¹Sigi Kaltenecker (Loop Organisationsberatung) & Bent Myllerup (agile42): Agile & Systemic Coaching

http://www.scrumalliance.org/community/articles/2011/may/agile-systemic-coaching

²Karl Weick and Kathleen Sutcliffe: Managing the Unexpected—Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty (Second Edition, 2007, Wiley), page 80.