There seems to be a large misunderstanding around what it means to be an agile coach. Coaching is well understood, and the largest providers of agile coaching certifications have converged and agreed on the definition. Still the agile coach is constantly being deflated into something like a multi-team Scrum Master, and agile coaching companies have difficulties explaining the value they will bring to their customers. What’s going on?

With this blog post, we’re going to take a hard and in-depth look at the agile coaching profession and straighten out some of the misconceptions. You will hopefully find a clear and understandable explanation of what an agile coach is and isn’t, what an agile coach does (and doesn’t do), what value an agile coach will bring to the organization, as well as some tips and tricks on how to become an agile coach.

What makes coaching so magical is that it is an intensely personal experience for the coach. For a personal insight into one of the most rewarding professions available, watch the recording of our Webinar: A Personal View on Professional Coaching.

Why you should trust me

I’ve worked as a professional agile coach since 2008, and have well over 12,000 hours of agile coaching and 1,500 hours of agile training under my belt. Every year I’m racking up between 600 and 1,000 hours of actual honest hands-on agile coaching, in addition to training, writing, speaking and mentoring.

I’m the proud owner of a Certified Enterprise Coach® (CEC) certification since 2015, and an active member of the team that reviews and accepts Certified Team Coach® (CTC) applications at the Scrum Alliance. In other words, other highly skilled agile coaches are of the opinion that I know agile coaching, and they trust me in guiding and assessing candidate coaches.

Further reading: Martin is one of the authors of The Hitchhikers Guide to Agile Coaching which you can download for free.

What is an agile coach?

An agile coach is a servant leader who helps organizations transform towards higher levels of agility. Agile coaches use coaching and facilitation techniques plus complex management methods to help the client organization see and understand what’s going on, find their own solutions to their problems, and enact those solutions.

According to Wikipedia, coaching has its roots in the word “coach”, meaning “…to transport people from where they are to where they want to be”. The coach is merely helping the client on a journey of self-discovery and improvement, and all solutions must come from the client.

In contrast, an agile coach is expected to bring both expertise and experience in the subject matter. This takes careful balancing between coaching, teaching and mentoring on one hand, and consulting, advising and contracting on the other. We could perhaps talk about “transforming” rather than “transporting”, as it implies that the coaching subject needs to actively change into something new and different.

Complex management methods are necessary because organizations are complex. I won’t go into the topic very deeply here, but the key point is that you can’t design a complex system up front. Instead you need to let it grow, observing what emerges and either strengthening or dampening what you see. An agile coach tries to “nudge” the organization towards a better way of operating (which presumably involves lean and agile methods), and the direction of change is more important than the goal. By doing interventions of various kinds, an agile coach can generate small but permanent changes in how the organization behaves. Often the results are different from what you imagined initially.

Agile coaches work at varying levels in the organization, but always in settings where there’s at least a handful of teams that need to organize themselves effectively. The field of work is large, including products and services, skills and roles, the organizational structure, IT infrastructure and workplace services, agile/lean management processes, the facilitation of strategy creation and implementation, and much more.

In a traditional organization, agile coaches are often positioned directly above the Scrum Masters in the hierarchy, or sometimes in a separate unit that provides e.g. process development services to other units. In flat or teal organizations the lines are more blurred, but agile coaches generally have the capability to take on larger responsibilities than Scrum Masters do.

What does an agile coach do?

An agile coach will coach, obviously, but also teach and mentor people. They help visualize what is going on, and act as mirrors to the organization, helping people see things as they are. Agile coaches facilitate work, lead workshops and meetings, and help people make good decisions. They also grow new Scrum Masters and new agile coaches, by teaching and mentoring potential candidates in the organization, by showing them the ropes (a.k.a. role-modeling), and by living the agile values.

Why is coaching so valuable for the target organization?

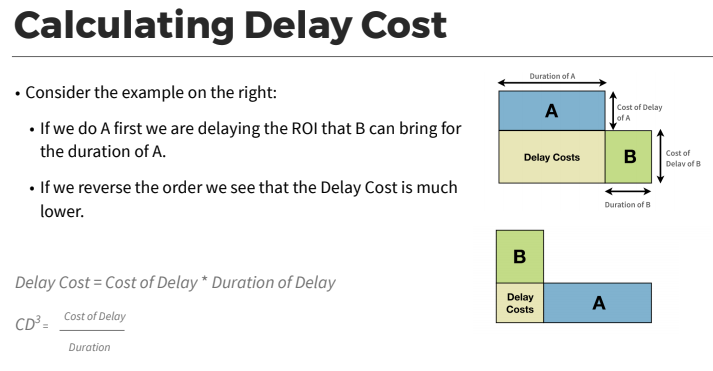

Fundamentally, companies need to make more complex decisions at a faster pace than before, which can only be achieved using distributed cognition and decision-making. Scrum and Kanban, with their short feedback loops and focus on quality, will take you in the right direction. Without self-organization the teams just won’t fly: self-organizing teams are more motivated and more proactive, and they can make better decisions. This is exactly what companies need today, and agile coaches help them achieve it.

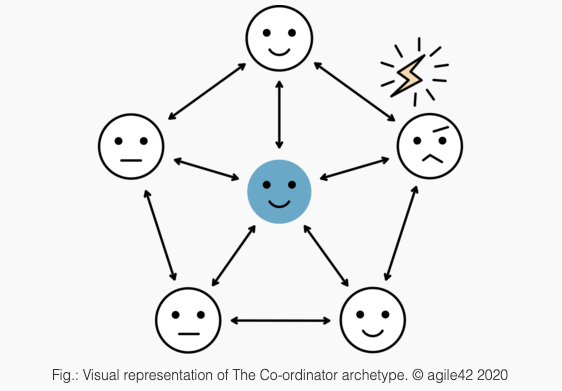

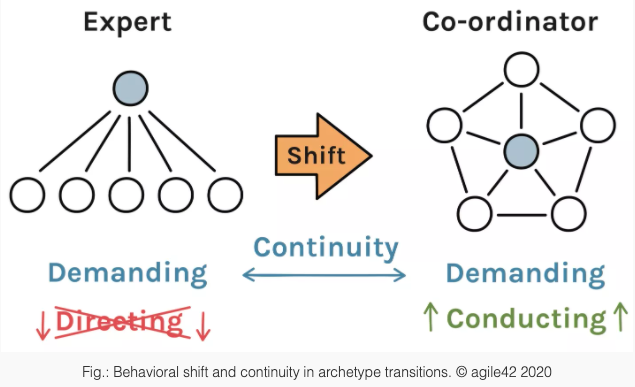

In order to become more self-organizing, teams need the right kind of leadership. We’ve found coaching, envisioning, conducting and catalyzing leadership styles work better than styles that are controlling, commanding, demanding or pace-setting. The latter styles are more effective in the short term, but pull decision power away from the team and to the manager. In the long term they will reduce the level of self-organization.

As most mid-level managers are under pressure to deliver, they do whatever they can to get stuff done. Coaches are needed to teach team members how to collaborate and make decisions, and to teach managers how to lead self-organizing teams and drive continuous organizational improvement.

Agile Coaching Skills

Being a successful agile coach requires a large number of different skills. Most people find it comparatively easy to learn e.g. agile and lean thinking and related practicalities. There’s plenty of books around, and you can find correct answers for many questions, and good trade-offs and guidelines for many others. In Cynefin terms, this is the ordered (simple or complicated) domain.

Learning the soft skills — how to become a good coach — is more difficult. Coaching is often complex and sometimes chaotic: you are listening and driving the situation forward by asking questions and choosing topics that serve the needs of your audience. You may need to challenge them or open new areas of thought. To do this effectively, you will need to act and react in ways that don’t necessarily come naturally to you.

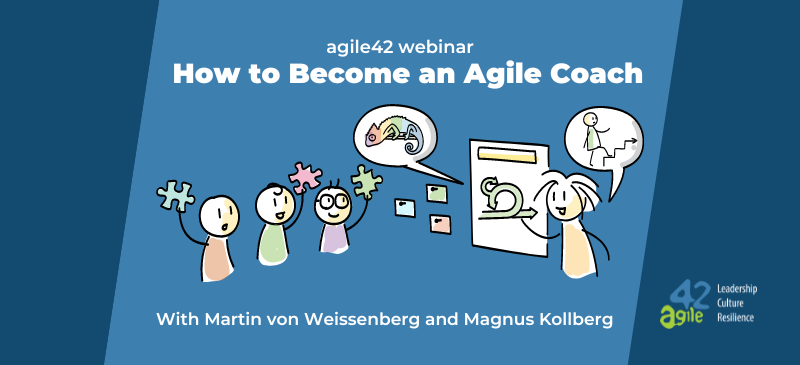

Below, I’ve listed a number of skills that I think a good agile coach should have. Luckily these skills are widely applicable, and most people will find them useful regardless of where their careers take them. Every team leader will benefit from coaching skills, every product manager should understand the ideas behind Lean and Agile, and so on.

- Coaching skills — The International Coaching Federation defines coaching as “partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximise their personal and professional potential”. This requires a number of soft skills that enable you to engage in intelligent and structured conversations that help the client organization change for the better. This is difficult, and new agile coaches often lack the requisite coaching skills. (We’ll dig into this problem later in the blog post.)

- Agile and Lean knowledge — The theories, thinking models and practises you need in order to become (more) agile. Because agile coaches should be able to teach others, their own understanding must be very good. Luckily, Lean and Agile knowledge is not too difficult to pick up, and most people get it straight sooner or later. If you are working with a big agile model, keep in mind that the underlying assumptions may not be valid for all organizations.

- Technical, business and leadership skills — As an agile coach, you will find yourself in situations where you need to help a group of people with agile practices specific to their role. This could include deploying continuous integration, setting up a project portfolio board, or helping managers to understand servant leadership. You don’t need to be expert in all these areas, but the more you know, the larger your impact can be.

- Facilitation skills — How to make it easy for people to do what they need to do. As a good facilitator, you provide a clear process and guide people towards their goal without injecting your own opinions or content.

- Teaching skills — An agile coach often needs to transfer a lot of new knowledge effectively, while respecting the fact that the audience consists of grown-ups. You also need to understand when some teaching is necessary, and how to assess the results afterwards.

- Self-awareness, self-reflection and self-improvement — A good coach is constantly looking for weak spots and is resourceful in finding ways to improve. For example, if you feel uncertain about your ability to deliver training (self-awareness), you might instead organize courses with a professional trainer. At the same time, you can ask for permission to observe them, or perhaps co-train and get some feedback (self-improvement).

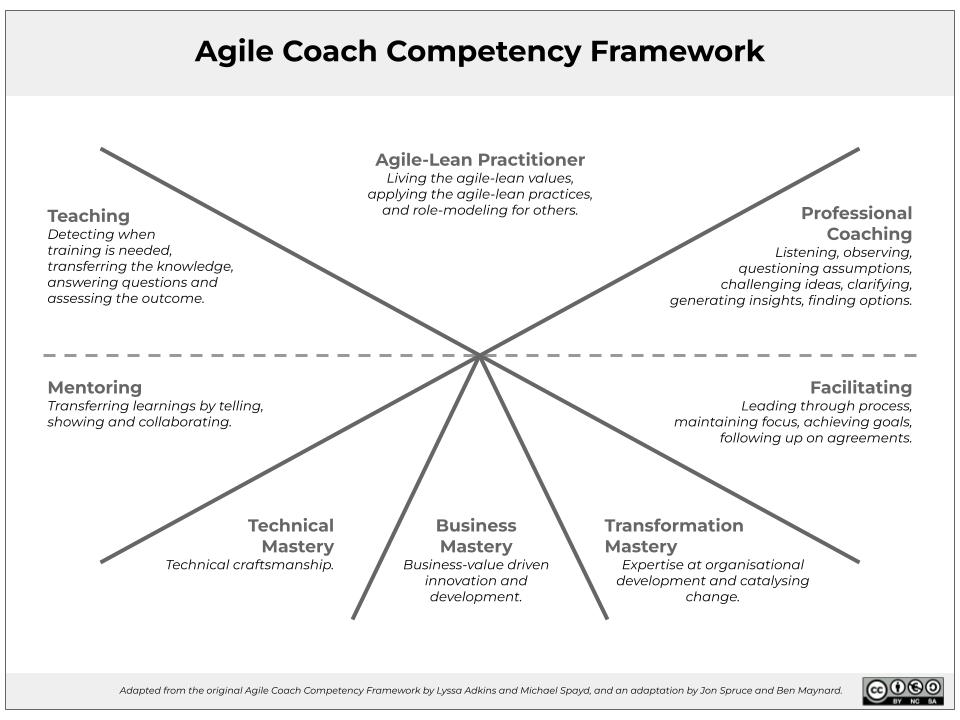

The list is not whipped up from thin air. It’s based on the Agile Coach Competency Framework by Lyssa Adkins and Michael Spayd, with clarifications from Jon Spruce and Ben Maynard.

The difference between a new agile coach and an experienced one

The difference between a new agile coach and a more experienced agile coach is that the latter has more techniques they can call on, is able to see deeper patterns, and is able to assemble and create new techniques on the spot. Based on my own experience from reviewing dozens and dozens of CTC applications, I’ve tried to conceptualize this into three dimensions:

- Width: How wide is your toolbox of methods and thinking models? This dimension is related to the Law of the Implement: if you only have a hammer, all problems look like nails. The more tools you have at your disposal, the better you can handle each situation. A newbie coach may have only a few techniques available, while an expert agile coach has a large library of methods they can refer to.

- Length: For how long have you collected experience? A newbie might need printed instructions, while a more experienced coach can run several meetings and workshops from memory. A true master is able to meld different methods and synthesize new approaches on the fly. This is also known as shu-ha-ri.

- Depth: How deep can you see? An agile coach should have the ability to see below the surface and identify holistic organizational patterns beyond the single-team context. If the team is not delivering running tested software reliably, they are often prevented by the constraints and expectations set by the surrounding organisation.

People tend to improve in all of these dimensions over time. Experience and learning comes through doing, but progress can be uneven and proceed in fits and starts. You can speed this up considerably by working in environments with an existing embedded agile mindset, where you will be able to observe good examples and pick up good ideas on a daily basis. Co-coaching especially can be very educational. Conversely, if you find yourself in an agile-in-name-only organization, you’ll find yourself picking up narrow thinking models and suboptimal methods.

As a CTC application reviewer, I should also mention that most problems tend to occur in two areas. Most of the rejected or deferred applications lack depth across the board: the capability to see larger organizational patterns is not there. The second most common reason is insufficient coaching skills.

Recommended online course: Agile Coaching Foundations

What kind of jobs can an agile coach find?

The vast majority of agile coaches work either as internal employees or as consultants, although there’s a lot of variation.

As an internal agile coach, your job is often to work with a specific department or a specific business unit, or sometimes a whole company, to help them become more agile. The line of business can range all over the map, but is often related to software development, IT or R&D. You can sometimes be a member of a specific department or business unit, or belong to a coaching department that provides services to other business units. The job is fairly stable, and during layoffs coaches are either the first or the last to go (which incidentally tells you a lot about the company). You also have an opportunity to follow the same company for several years to see the long-term impact of your work.

Consultants have more options, and I’ll list some of them below:

- You can work for one of the many software subcontracting companies that deliver “agile projects.” The work often revolves around helping your software development teams become more efficient, or teaching and coaching clients on how to work with an agile team. Sometimes you’ll also provide management coaching or agile transformation services for clients, e.g. in parallel with a digitisation project carried out by your software development colleagues.

- Being a freelancer might be an interesting option if you’re conscientious and business-minded and have a good personal reputation. It’s difficult for one-person companies to get large transition engagements, so freelancers often accept subcontracting assignments or join a cluster of like-minded people who can feed work to each other. The downside is that it can be difficult to find time for self-improvement (i.e. reading books and taking courses), and there may be limited opportunities for co-coaching with others.

- There are “boutique” consulting companies such as agile42 specializing in, for example, agile transformations or strategic agility. With increased mass (say, more than half a dozen coaches) comes increased stability: you can afford to invest in self-development and take time out between gigs. You will also generally see larger and more interesting client cases than a freelancer would, and have colleagues who you can mentor or get mentored by. (I personally think this is the sweet spot, but I’m probably biased.)

- Virtually all big consulting companies employ some agile coaches. Customer engagements depend on what the account managers sell. These companies are often working with one of the big agile frameworks (DAD, SAFe, LeSS, Spotify model, what have you), or have created their own methods and approaches. On the upside, there is often a step-by-step deployment process that brings clarity to everyone, and there are other coaches to work with and learn from. On the downside, the pre-defined engagement processes may be strict and leave little room for coaches to experiment and learn.

Be aware that some companies advertise for an agile coach, but then provide a role description that is closer to that of a Scrum Master, Agile Project Manager, Jira/TFS expert, or some kind of Agile-Do-It-All. This always indicates that the company doesn’t understand what an agile coach actually is. Many good coaches tend to refuse to accept such constraints. On the other hand, others can see it as an interesting challenge. It’s your choice.

There’s another common anti-pattern where an agile coach is expected to handle the operative duties for three or four teams in an organization, without Scrum Masters. By limiting the scope of the role and ensuring that the coach is busy running Scrum mechanics, the organization loses out on virtually all the benefits that an agile coach can bring in the first place. Again many good coaches refuse to take on this kind of assignment.

Beyond the opportunities listed above, you may occasionally find more specialized work. Agile training outfits sometimes have an agile coach on the roster, offering in-depth coaching courses or post-training support to the students. Venture capitalists have been known to hire agile coaches to e.g. roll out lean startup techniques. Management consulting companies sometimes need coaches with agile experience, to coach senior executives. And you might occasionally find a job ad from the Scrum Alliance or another non-profit in this domain.

How much does an agile coach earn?

The salary for an agile coach varies quite a bit. As a rule of thumb, an agile coach should look for wages similar to those of a Senior Project Manager or development manager, while an experienced lead agile coach or head coach should have a position similar to a Head of Department, with the appropriate compensation.

In flat or teal organizations, agile coaches can draw on their facilitation and coaching skills to show the value they are contributing to the company, which helps negotiate a good wage. As a freelancer, you should take what the market will bear. You bring a huge amount of value to your clients, so price your work accordingly.

That said, some of the main factors for the salary include:

- The cost structure of your country: For example, a coach in South Africa or India gets paid less than half compared to a coach in Northern Europe, but the costs of living are correspondingly lower.

- Whether you are an internal coach or a consultant: Internal coaches have compensation schemes similar to that of the other employees: a base wage plus perhaps a small (10%) annual bonus. A coach working for a consulting company can have a lower fixed wage, but a higher provision-based component. A freelancer is of course fully dependent on what they can invoice.

- Your level of experience, capabilities and credibility: As a junior agile coach or Scrum Master replacement, you will get bottom money. An established and well-reputed executive management coach can command fees that are substantially higher.

- The agile certifications you hold: Certifications are important, not only for the learning journey but also for the signals they send. By proving that you have the requisite knowledge and experience, you can land more interesting and better-paying engagements. On the other hand, you may also be seen as overqualified for simpler jobs. We’ll cover the topic of certifications in depth later.

- Whether you are also a (certified) trainer: Having two lines of business is better than having just one speciality and many agile coaches also work as successful agile trainers. Training and coaching are two separate skill sets, but they complement each other nicely and can open opportunities for theory-informed practice.

- The company culture: Regardless of whether you are an internal coach or a consultant, you will find that some companies have a better understanding the value and the benefits that an agile coach can bring. This will have an impact on the salary.

How to become an agile coach

Becoming a good agile coach is a long journey. There are no shortcuts, although you can speed it up by keeping in touch with the best people you can find. Below, you will find some ideas and suggestions.

Cultivate self-awareness and self-improvement

This is the basis of becoming good at anything, in fact. At all times, reflect on your own performance in the small and the large. Note the choices you are making, as well as the situations where someone else saw a choice that you didn’t. What went well, and what should you do differently next time? These are things you can reflect on immediately, while you grab a coffee after your meeting, or later in the gym, or on your commute.

Whenever possible, get direct feedback from your clients, teams and stakeholders. Consider using something like the return-on-time-invested (ROTI) method to get immediate feedback at the end of every meeting or workshop that you facilitate. You may want to talk to people you are working with to understand what you’re doing well and what you need to improve. How about collaborating with other agile coaches to get to-the-point feedback and second opinions? At the end of a time-limited assignment, you might want to conduct a formal “exit interview”. It can also be useful to sit down and think back over the last year or two, although it requires a bit more discipline. How are things working out for you? What changes do you need to make?

Coaches thrive in a human-centered team culture with a coaching leadership style. One implication is, unexpectedly, that your boss shouldn’t be your only source of feedback. A good leader of coaches would ask you to get your feedback mainly from the people you serve or work with. They would also task the whole team with figuring out their strengths and weaknesses together, and to come up with a strategy for improving their skills. Insofar as they throw in their own feedback and opinions, it’s just one data point among many others.

Enroll in ongoing education

Education comes in many different forms. This includes reading articles and books, talking with experts in the field, participating in conferences, observing masters at work, taking formal training, enrolling in post-graduate studies, or generally trying to achieve a self-assigned goal. You can also work towards a relevant coaching certificate, as that gives you a more focused checklist or curriculum.

Learning happens automatically to most people, but you can speed it up by applying focus. Take a moment to identify your current areas of interest, and then work to get an index of what is available. Who are the authorities in the field? What books have they written, what models and theories have they created? Whose work are they building on, and who is now extending their work further?

Get yourself a basic (agile) coaching certification

Even a basic certification will be beneficial, if it’s of the right kind and backed by a credible organization such as the International Coaching Federation, the Scrum Alliance, ICAgile, or any of the other associations mentioned in this blog post. agile42 offers the following agile coaching certifications:

Remember that not all ideas and concepts are equally reliable. Some work is well researched and backed up by logic and empirical results. To mention a few, I have high trust in the Lean product development concepts presented by Donald G. Reinertsen, and in Karl E. Weick and his work on organizational psychology. The same goes for the Cynefin sense-making model and related concepts by Dave Snowden.

Other ideas rest on shaky or non-existent foundations. For example, Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) and Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) have both been debunked as pseudoscience. I can’t recommend making them the basis of your career.

There’s a number of coaching schools that fulfill these criteria and are generally accepted in the agile coaching industry, including:

When it comes to Scrum, Kanban, Lean, various scaled processes etc. there’s a large number of trainings on offer, with and without certifications. When choosing an agile training, keep the following in mind:

- The best trainers are also practicing coaches. The combination of practical experience and theoretical knowledge is hard to beat.

- The Scrum Alliance sets the highest bar for their trainers: it’s notoriously difficult to become a Certified Scrum Trainer (CST). For this reason their Scrum courses are generally better than the competitors.

- If you want or need certification, be sure that you pick a good certification authority. A good certification is an asset; a bad certification is a liability.

Get coaching experience

It’s been said that it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill. Some people say that the effort must be thoughtfully and diligently applied, while others think it’s more of a general guideline, and yet another group contends that all of this is just a gross oversimplification. Regardless, we can all agree that you must invest time, effort, practice and reflection to become an expert. So start early — preferably yesterday — and remember that it’s never too late to turn failures into learning experiences!

Try to maximize diversity in your work. This means working with all kinds of industries and technologies, small companies and multinational enterprises, startups and NGOs, in your home country and on the other side of the world. Each additional environment and business domain you get acquainted with will give you new challenges and new experiences.

In most industries, for example, you will find constraints and regulations that force people to work in certain ways. For example, banks and insurance companies must cope with heavy regulation and the desire to be perceived as reliable by their clients. Mobile games are less regulated and people will accept some level of defects. The embedded software in a pump at the bottom of a well may never be updated, while updates to a web app can be automatically tested and deployed as soon as the developer hits Ctrl-S.

Gaining experience requires self-reflection and improvement, as mentioned above, but also a certain amount of audacity and serendipity — a willingness to get out of your comfort zone and try new things, even though you might not succeed at first. As agilists we should be well prepared to work in small batches, inspect the results and adapt for next time. Einstein has a number of great quotes on this topic, including “A person who never made a mistake never tried anything new” as well as “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.”

As you are collecting experience, make sure that you get to do actual agile coaching. This is not the same as being a Scrum Master for a team, or driving the Product Owner community. Coaching Scrum Masters and leaders in multi-team settings requires deeper and wider knowledge, including the ability to teach and mentor people.

What certifications are relevant?

There’s a lot of certifications that sound like they could be useful for an agile coach. But how do you know which ones are worthwhile and which are not? Why spend a lot of money and time on some specific certificate, when you can get another certificate quicker and for a fraction of the price?

The answer is in signaling, a concept originally introduced by Nobel-prize economist Gary Becker. He argued that it’s very difficult to understand the talents or skills of any person, so prospective employers would use university degrees as a proxy. Your B.Sc. or M.A. or Ph.D. sends a signal about you — and so does just being accepted into an Ivy League university, even if you drop out later.

Having a good agile coaching certification signals that you know your stuff. It tells people that you have invested significant time and resources in learning the right skills. It shows that a review panel, consisting of expert agile coaches, have inspected your credentials, assessed your skills, and found you worthy.

Recommended for you: View agile42’s agile certifications

Becker’s distinction between elite and non-elite universities is also useful. In this case the “Ivy League” of agile coaching institutions consists of only three organizations: the International Coaching Federation, the Scrum Alliance and the International Consortium for Agile.

Other agile coaching certificates can certainly be found, ranging from the questionable to the outright embarrassing.

What coaching certifications should I avoid?

Certifications related to a specific process framework are considered mildly suspicious. Coming in with a pre-defined solution is in conflict with the principles of coaching, meaning that those certifications are weak or confusing signals. People who don’t know better may be impressed, but those in the know will look for further signals.

Avoid all coaching certifications that can be had immediately through a multiple-choice online exam. First, coaching is a complex skill that is extremely context-dependent, and there is no automated way of assessing your skill level. Multiple-choice questions are totally inappropriate for the job: the questions are either leading or the difference comes down to nitpicking semantics. Free-form answers and essays work better, but can’t be graded by computers. They must be assessed and graded by human experts, which increases the cost and the lead time.

Second, people can and will cheat on these tests. If you get stuck on a particularly difficult question and ping a friend about it, who will ever know? If you buy the answer sheet online, or pay someone to do the exam for you, who will ever know? And if you did the exam honestly and properly, who will ever know?

Such certifications are not only worthless, they are a liability because they send the wrong signals. People will think that you are either ignorant or gullible, or trying to fool them.

Pure coaching certifications

The International Coaching Federation is the gold standard for systemic coaching globally. There are a number of regional organizations that apply the same level of rigor, including the European Mentoring and Coaching Council (EMCC) and the Association for Coaching (AC). If you can present even an entry-level certification from any of these, then people will take it as given that your skills are sufficient for agile coaching.

Certifications specific to agile coaching

There are two reliable sources of agile coaching certificates: Scrum Alliance and International Consortium for Agile.

The Scrum Alliance provides two certifications directly applicable to agile coaching: Certified Team Coach® (CTC) and Certified Enterprise Coach® (CEC). They are both pure competence assessments with a self-guided learning journey, and there is a lot of overlap in the requirements as well as the application process. You will need to structure the learning process yourself, working on your own to ensure that you meet the requirements — sufficient coaching skills, hands-on experience, training and outreach, and so on — and stay in contact with mentors who can give guidance and advice. When I applied for the CEC, it took me two years.

Together with the Certified Scrum Trainer® (CST), the CTC and the CEC are considered “guide level” certifications by the Scrum Alliance. This comes with certain rights and obligations: CTCs and CECs are for example allowed to confer CSM certifications through coaching, just like the CSTs can do through training. This also means that the Scrum Alliance applies stricter criteria than others.

It’s worth mentioning that Scrum Alliance is a non-profit organization that doesn’t have the goal of making money. They can afford to take a serious approach to certifications, and this is clearly visible especially at the guide level.

The International Consortium for Agile, also known as ICAgile, is backed by several good names in the agile coaching industry. They are generally considered a reliable and reputable provider of certifications. Similar to Scrum Alliance, they provide two relevant certification tracks, Team coaching and Enterprise coaching. In contrast with the Scrum Alliance certifications, ICAgile is more structured: you need to take three specific courses, and then pass a competence assessment. There is little overlap between the team and enterprise track though, the courses are for example totally different.

Do you want to become an agile coach?

Great! Regardless of where you are, making the decision to start is the first step of the journey. Dig up the Agile Coach Competency Framework and do a self-assessment. Where are your strengths? What are your weaknesses? Browse our training, pick a skill, and keep moving on your journey.