Almost exactly one year ago I stood in the kitchen waiting for the coffee water to come to the boil. Watching water coming to the boil is somewhat boring and my idle eyes dropped onto a towel someone had brought in, which said “Happiness is not a goal, it’s a way of life.” Still waiting for the hot water I digested this piece of information, and it dawned on me that, although I myself of course have no misconceptions about agility whatsoever, so many people have got agile wrong. They think agility is a goal, but it’s really a way of life. Hmm, I thought, I must write this down! As if waiting for this moment the boiler clicked off, and my insight was pushed aside by the imperative of making coffee.

What you are reading now is the first part of a series of blog posts on change, long in the making. I am writing this from the perspective of agile software development. Change is the core of agility, and you can’t be agile if you are not prepared to change and benefit from change. Being agile is to live with change, for change, and to be able to continuously create change. Not only change in the product, but in the processes and work agreements, and in the organization itself. Change needs to be embedded in the organizational culture — yes, even organizational change, even though it may sound like an oxymoron.

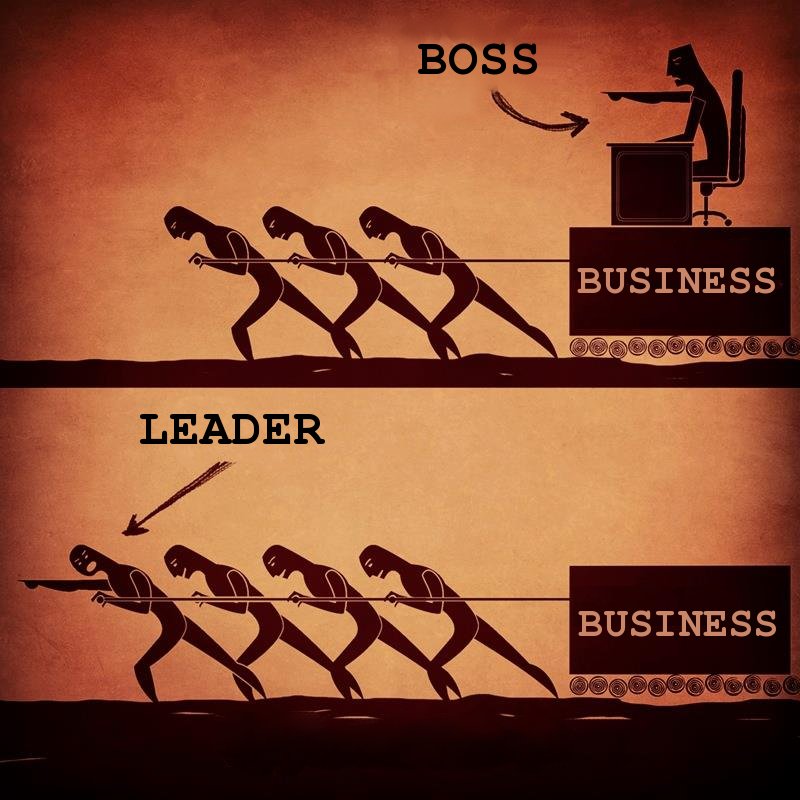

Naturally then, understanding change is very important if you want to work effectively as a servant leader, perhaps a ScrumMaster. Leadership is much about paying attention, observing and listening, making sense of situations and helping others understand what is going on, then letting people try out their own solutions. Through positive experiences the new methods will eventually stick and become culture.

I haven’t planned out the rest of the blog posts in detail yet, but the idea is to gradually progress from understanding change in theory and in practice towards understanding how to introduce change, apply change and perhaps guide it when it happens. We will also look at a number of larger agile frameworks from the perspective of change. There is enough material here for at least three semilong posts, so bear with me.

By the way, the models and ideas that I describe here are not my own. I have picked up a number of concepts from various sources over the years and retained those that I feel are useful. They help me make sense of what change is, how it propagates and how you even might be able to gently guide it sometimes.

Buy-in: Internal vs. external change

When the millenium was still pretty new, I worked as a process engineer in a medium-sized software consulting and subcontracting company. Starting from a very slim ISO 9000 -certified process, we worked in a group of three to develop our subcontracting processes towards CMMI level 3 (and also achieved the target in 16 process areas, but that is a different story). We worked on a small number of elements at a time and tried to finish each process element and deploy the results as quickly as possible.

Predictably, our project managers were not too thrilled by the changes. On the other side of the corridor sat a couple of trusted go-to guys that I knew would help me out in a pinch, but piloting the new changes with them was always a hard sell. It took months to talk them around to the new ways of doing things. But sometimes they would surprise me by developing their own tools and templates. Why was that?

One way to describe this is through buy-in. If a person doesn’t understand the new methods or think that they are better than the old ones, nothing will change. However if the person can participate in exploring and generating ideas, it is easier for him or her to buy into the idea, and the threshold to picking it up is much lower. And sometimes you find that somebody gets all excited over a new method, and wants to deploy it directly.

In general local knowledge is seen as more reliable than remote knowledge, and opinions more reliable than empirical data (Rainer et al., 2003). In plain language, the work done by the Process Development Unit and knowledge presented in academic research reports is perceived as less credible than the opinions and experiences of a teammate. Internally driven change meets less resistance than externally driven change. (If you don’t trust the article by Rainer et al., just take my word for it!)

In my case I was able to impose myself as a teammate to the project managers. But because I did not do the same work as they did, I was not really a project manager. My experiences and opinions did not carry enough weight and I resorted to the less credible and thereby slower method of presenting theories and models, many times using actual live project data to exemplify the concept.

How do you internalize change? We’ll discuss that later in this blog post, and will return to the topic in future posts. But for now, lets look at… FEAR!

Reactions to change: the lizard brain

The second lesson I want to bring up here is that all humans have a hard-wired notion that change is dangerous. In the jungle or on the veldt, those who spot telltale changes and avoid them are the ones who survive.

It pays off to over-react, to have a slightly lower panic threshold than one would think necessary. This is because those who scram off immediately use up more energy, but may live to see another day. But those who hang around to check that the waving grass really conceals a man-eating saber-tooth tiger don’t always get the chance to scram off. And so we have evolved an instinct for getting out of dangerous situations. Change and fear are connected on a quite deep level in our brains.

Some years ago I picked up a concept from a marketing guy named Peter Schneider. It’s simply called “the lizard brain”, and like all models it is wrong: it’s a simplification of reality and thereby full of holes and errors. However, I have found it very useful. It explains some of the reasons why people fear change, and also helps make sense of why people react as they do in the face of change.

The main concept of the lizard brain model is quite simple. When subjected to a threat of some kind — a threat to your habits, your territory, or your existence — people go into panic mode and will either fight, flee or freeze.

The name “lizard brain” comes from fact that panic reactions are handled (mostly) by the amygdala, which can be found just above the brainstem in all invertebrates. We share this with all mammals, birds and, indeed, with lizards.

When an invertebrate animal — a homo sapiens for instance — is subjected to a strong threat, the amygdala causes an immediate primal reaction. This is not a simple reflexive action: reflexes typically only yank a couple of muscles. But the primal reaction is still well below rational thought. In a dangerous situation, standing around considering your options is not a good, uh, option. In fact, one could say that the upper brain functions are simply subverted, disconnected by the amygdala. People suffering from primal fear are not only unreceptive to rational arguments but incapable of rational thought.

Perhaps an example would be in order here. My own strongest experience of primal fear happened at around the age of ten, when I walked on a sandy road and saw a large slavering dog running towards me. I was so scared that I just screamed at it, ready to fight for my life. (In terms of the lizard brain model, this is a fight-for-existence reaction.) Luckily the dog was as scared as I was. It did a somersault, turned on the spot and ran away. Immediately afterwards, my heart pumping adrenaline at 180 bpm, I felt ashamed of losing control, but also the deep satisfaction of winning a fight.

Interestingly enough the lizard brain is also activated in prolonged situations of fear or anxiety, as is the case in e.g. agile deployments. Case in point: “We will pilot Scrum in the organization and your team is the best candidate!” In other words: “We say you Scrum.” Ouch! How do people interpret this?

-

To some people agility is a threat to their habits. Many are accustomed to working in the warm fuzzy zone of “there are some last-minute problems but I think I can possibly get it done by next week Thursday”, also known as “90% done”. Others like to work alone and keep information to themselves, and see the increased transparency as a threat. Yet others feel that the daily standups are stupid — it takes weeks to implement this feature, why should I report every day?

-

Some people see Scrum as a threat to their territory. Many of them are former project managers that are now relabeled ScrumMasters or Product Owners and find that they have lost a large portion of their power. Or perhaps they are software architects irritated by the fact that teams are doing unapproved changes directly into the code base?

-

Some people see agile methods as a threat to their existence in the organization. These include line managers whose teams are suddenly self-organizing, or testers who learn that all testing will soon be automated, or specialists that have carved out their own narrow niche.

To the 95% who are not directly involved in driving the agile transition, Scrum is a cause of anxiety or outright fear. How do they respond?

-

Fight! Direct and indirect attacks. Badmouthing. Fear, uncertainty and doubt. Passive-aggressive behavior in the Scrum meetings. Appearing to play along for a while, then a sudden explosion of this-will-never-work. And so on — the examples are countless.

-

Flee! Some people grab the opportunity and move to other teams or escape the company altogether. The decision to flee is often made early, after enduring perhaps two or three weeks of Scrum, although it can take months for the fallout to appear. By that time people have made new commitments, signed new contracts, and the decision is very hard to reverse.

-

Freeze! A surprisingly large number of people seem to lose their drive and become unable to produce anything of value for months on end. They are moving the mouse and tapping on the keyboard but nothing real comes out.

In almost every team I work with, I can find examples of fighting and freezing. Sometimes, but luckily very seldom, also of fleeing. This model has helped me make sense of why people behave irrationally during an agile deployment.

As a manager or ScrumMaster of a piloting team, it’s your job to navigate them past this stage of anxiety. The main problem is how to do that when people are not thinking rationally. Let’s take a look at a third model.

Cultural change: the pyramid of results

Traditional management methods are focused on guiding and synchronizing the actions people do. The thinking goes that actions produce results, and if we want to get better results or more consistent results, we need to improve the actions people do. We can do this sometimes by standardizing, perhaps by measuring, perhaps by modeling and planning, maybe by setting up KPIs and targets.

We could also introduce the Project Manager role to plan and synchronize the actions of several people, and the role of Quality Manager to measure the results and improve the tools and processes. What if we want to make a more revolutionary change? Why, we set up a change program.

Unfortunately change initiatives are unlikely to succeed. According to Towers Watson, 75% of change initiatives fail to have any sustained long-term effects. I used to think that the 70% level of failure in software projects was astonishingly high, but this is even worse! Thoughtfully Towers Watson provides a list of causes; predictably it includes things like unrealistic goals, uncommitted CEOs, insincere senior managers, and the scourge of short-term thinking.

Needless to say, these symptoms are all likely to appear in a failed change initiative, but if you want to make the initiative succeed then attacking the symptoms is futile. According to the abovementioned study, 87% of the respondents train managers to manage change, but only 22% say that the training had an effect. You need to dig deeper. And so, let me introduce the “pyramid of change”.

The driving idea behind the pyramid of change is that what people do and how they do it is strongly influenced by their beliefs and value systems. If the actions and expected results are in line with their values and beliefs, they will happily and voluntarily do what it takes to get the results done. If not, they see little point in the exercise and will grudgingly carry out the task.

Where do people get their values and beliefs then? Well, from experience. From trying out things themselves, from observing other people, and from talking to other people about their experiences.

The Results Pyramid is © Partners in Leadership LLC.

The upper half is about “hard skills”: guiding and scheduling actions, measuring the results, managing risk. The lower part of the pyramid consists of the company culture, which requires “soft skills”: leadership, politics, managing expectations, shaping beliefs and making sense of experiences. Managers are well trained to work in the upper half of the pyramid, but as a leader in a change situation you need to shift your focus.

If you want your organization to change, you must create new experiences. You must show people that the new methods work in practice, tell them fairy tales and horror stories about how other teams have succeeded or failed, and use new thinking models to help people understand what is happening. As they gain experience from working with the new methods, they will start trusting the new ways of working: in other words, they will start changing their belief system.

Summary

In this post I presented three models of change. There are more to come, and I will bring them up in future posts. However, let me first tie up the three models by returning to my first example of developing processes towards CMMI level 3.

As a process developer I saw that people were reluctant to take new methods into use. I tried to repeat my rational arguments over and over again, and I felt that people were slowly, slowly becoming more receptive over time. Back then, I thought that it was a question of understanding the new method, and that this could be achieved by teaching and demonstrating.

In hindsight I’ve understood that things work differently. Project Managers were afraid of the changes I were proposing, and felt anxious about taking them into use. They did not necessarily respond well to my preaching: they became more receptive because they were getting practical experience from using the new methods, learning that the threat is really smaller than they thought. In other words, regardless of how much you tell them that the saber-tooth tiger won’t bite, they need to see by themselves that the tiger is continuously NOT attacking them before they can stop thinking of it as a “foe”… and perhaps someday start thinking of it as “friend” or “ally”.

References

A. Rainer, T. Hall, and N. Baddoo. Persuading developers to ’buy into’ software process improvement: Local opinion and empirical evidence. In Proceedings of the 2003 International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering (ISESE’03), 2003.

The well-established Agile Testing Days will reach Den Haag on February 13, 2014 for a one-day conference and we’re very happy to be sponsor of this great meeting of Agile-minded software testers. Our founder and strategic coach Andrea Tomasini will deliver a keynote presentation controversially titled Agile Testing is nonsense, because Agile is Testing.

The well-established Agile Testing Days will reach Den Haag on February 13, 2014 for a one-day conference and we’re very happy to be sponsor of this great meeting of Agile-minded software testers. Our founder and strategic coach Andrea Tomasini will deliver a keynote presentation controversially titled Agile Testing is nonsense, because Agile is Testing.

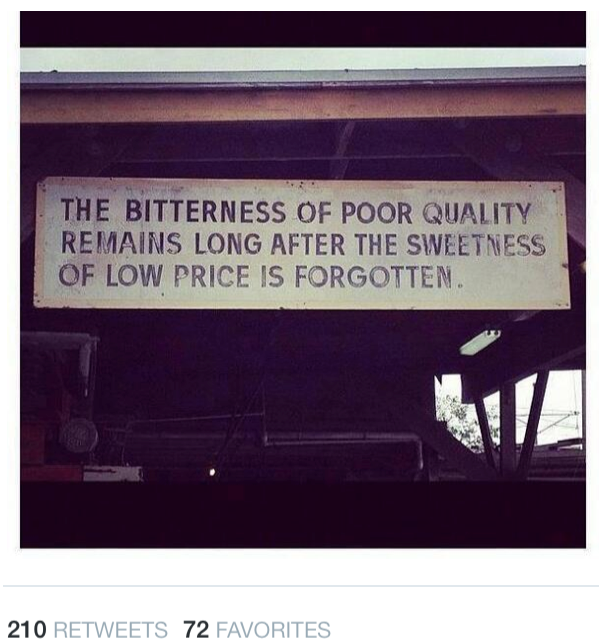

I am not a very active twitter user, so I was quite amazed it was retweeted over 200 times! Apparently the quote on the picture resonated with a lot of people, which inspired me to write this post. I also did some further research on the origins of the quote. It’s not clear who was the original author, but some sources attribute it to Benjamin Franklin. In the picture the quote seems to be hanging in an old saw-mill, but it turns out that around 1930 many companies had this statement as their motto, to emphasise they were building products to last.

I am not a very active twitter user, so I was quite amazed it was retweeted over 200 times! Apparently the quote on the picture resonated with a lot of people, which inspired me to write this post. I also did some further research on the origins of the quote. It’s not clear who was the original author, but some sources attribute it to Benjamin Franklin. In the picture the quote seems to be hanging in an old saw-mill, but it turns out that around 1930 many companies had this statement as their motto, to emphasise they were building products to last. Quality is Free

Quality is Free